Compiled by:

Marcus and Paul Hayes

The nineteenth in our series of features telling the story of the creation of Doctor Who, and the people who made it happen.Production on the new series was progressing. The main cast were under contract, scripts were being finalised, and work was well under way on the title sequence.

The nineteenth in our series of features telling the story of the creation of Doctor Who, and the people who made it happen.Production on the new series was progressing. The main cast were under contract, scripts were being finalised, and work was well under way on the title sequence.

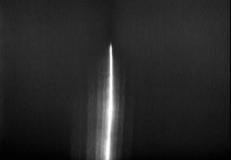

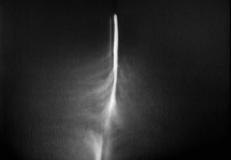

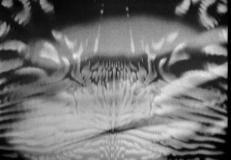

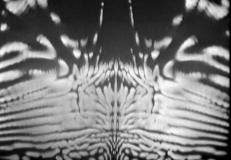

An experimental session, testing new electronic effects for the series, had originally been planned for Friday 19th July, and it finally took place on

Friday 13th September 1963, exactly 50 years ago today.

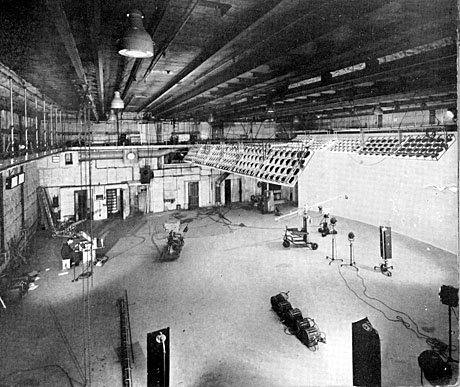

The place was Lime Grove Studio D, the studio which would become the main home of Doctor Who for its first few years of production. The main purpose of the day was to try to achieve an effect of the Doctor's spaceship, the TARDIS, dematerialising. The TARDIS prop had been built in the shape of a Metropolitan Police box, as specified in the script by

Anthony Coburn. Police boxes were a common sight in 1960s London, with more than 650 in the capital. They played an important role in police work, providing a means of communication in the days long before the two-way radio. Designed by Metropolitan Police Surveyor Gilbert MacKenzie Trench in 1929 specially for the London police, the boxes were made of concrete with a door of teak. The interiors of the boxes normally contained a stool, a table, brushes and dusters, a fire extinguisher, and a small electric heater.

The replica, built by the BBC, was made of wood. On arrival at the studios on the morning of 13th, though, it was found that the prop was too big to fit into the service lift needed to transport it to the studio on the fourth floor.

One of the crew assigned to the studio that day was

Dave Mundy, who remembers:

On Friday, 13 September 1963, crew 1 was allocated to Studio D, Lime Grove, 0930-1745, programme title – ‘Dr. Who experiment’. Some experiments involved smoke generators and some electronic effects. Studio D still had the old CPS-Emitron cameras which were renowned for producing a vision 'peel-off' when pointed at a bright light... Studio D had the old tungsten 4-lights so it was very hot!

Meanwhile, after the months of behind-the-scenes work that had so far been carried out on

Doctor Who, details of the new series were finally beginning to be released to the public for the first time. The BBC had held a launch for its autumn television season with Controller of Programmes

Stuart Hood in Blackpool on

September 12th 1963, and the following day a report on the event and the new season's shows appeared in

The Times newspaper. The article mainly concentrated on the return of the controversial satirical series

That Was The Week That Was, but at the end mentioned in passing:

A new family series, "Dr. Who", which borders on science fiction, will be screened on Saturdays...

While only a small acknowledgement in a report on a whole season's worth of programming, this is believed to be one of the first mentions - if not

the first mention - of

Doctor Who in the media.

Progress was being made on the scripts for the new series. The launch date had now been delayed for a further week and the show would now debut on

Saturday 23rd November 1963.

On

Monday 16th September, script editor

David Whitaker updated the production team on the latest running order for the first few months of the show. The first three stories were unchanged. The series would begin with

Tribe of Gum, followed by

The Robots, and

A Journey to Cathay. A story based on miniaturising the crew, favoured by Whitaker, was now slotted in at number four and had been assigned to author

Robert Gould.

The fifth slot was now assigned to

Terry Nation's story

The Mutants. It had been commissioned by Whitaker after Nation submitted a storyline entitled

The Survivors about a race of aliens who had survived an apocalyptic war. Nation's agent,

Beryl Vertue, the future mother-in-law of showrunner

Steven Moffat, had succeeded in negotiating a higher-than-usual fee for the writer and he was paid £262 per episode.

The sixth story had now been allocated to another established writer,

Malcolm Hulke, who had proposed two stories for the series. One,

The Hidden Planet, featured a world identical to Earth but hidden on the opposite side of the Sun. The other, the one that was accepted, was set in Roman Britain, just before the departure of the occupying forces.

Rex Tucker, who had been due to share directing duties with

Waris Hussein, had left for a holiday in Majorca and it was decided he would not return to the project. Tucker had never been happy working on Doctor Who and it was agreed that when he returned from holiday he would move to other projects. In his place the young but experienced staff director

Christopher Barry was pencilled in to direct the second and sixth stories of the series.

Richard Martin was assigned the fourth.

Whitaker set out his thoughts about the series as follows:

These six stories, covering thirty four episodes, are, as has already been stated, not finalised - however they do provide a statement of flavour and intention. The first, second and third serials have been commissioned and are in various stages of development - the first being complete, the second being written in draft, the third in preparation and the fifth delivered in draft. Serials four and six are in discussion stages.

Doctor Who Story Plan - Tribe of Gum: Written by Anthony Coburn. Directed by Waris Hussein

Four Episodes. The story begins the journey and takes the travellers back to 100,000BC and Palaeolithic man. In this story the 'ship' is slightly damaged and forever afterward is erratic in certain sections of its controls. - The Robots: Written by Anthony Coburn. Directed by Christopher Barry

Six Episodes. This story takes the travellers to somewhere in the 30th Century, forward to the world when it is inhabited only by robots. - A Journey to Cathay: Written by John Lucarotti. Directed by Waris Hussein

Seven Episodes. The travellers join the explorer Marco Polo on his Journey to Cathay. - Miniscules [sic] story. Written by Robert Gould. Directed by Richard Martin

Four Episodes. The TARDS transports Doctor Who back to 1963 but reduced in size to one sixteenth of an inch. - The Mutants. Written by Terry Nation. Directed by Waris Hussein

Seven Episodes. The TARDIS crew land on a planet inhabited by survivors of an atomic war. - Story Six: Written by Malcolm Hulke. Directed by Christopher Barry

Six Episodes. The travellers are set down in AD400 where the Romans are just about to leave Britain. The crew are involved in a struggle at a time when the blank pages of history occur, in an adventure full of excitement and action.

With a pilot planned for recording on Friday 27th September, work had been completed on the score for the first story. The incidental music was written by

Norman Kay, a well-known television and film composer. The music was performed by a group of seven musicians and recorded at the Camden Theatre on the evening of

Wednesday 18th September.

SOURCES: The Handbook: The First Doctor – The William Hartnell Years: 1963-1966, David J Howe, Mark Stammers, Stephen James Walker (Doctor Who Books, 1994); BBC Prospero

A Doctor Who-themed trailer promoting the return of comedy panel quiz show Have I Got News For You has been made available to view online by the BBC.

A Doctor Who-themed trailer promoting the return of comedy panel quiz show Have I Got News For You has been made available to view online by the BBC.

The twenty-second in our series telling the story of the creation of Doctor Who, from conception to broadcast.

The twenty-second in our series telling the story of the creation of Doctor Who, from conception to broadcast. However, it was an episode that would not be transmitted on British television for another 28 years.

However, it was an episode that would not be transmitted on British television for another 28 years.

Doctor Who was to be recorded in Studio D at Lime Grove in west London. Opened in 1914 by the Gaumont Film Company, Lime Grove was a film studio converted for television. Bought by the BBC in 1950, it would be home to some of the nation's most-loved programmes for over 40 years.

Doctor Who was to be recorded in Studio D at Lime Grove in west London. Opened in 1914 by the Gaumont Film Company, Lime Grove was a film studio converted for television. Bought by the BBC in 1950, it would be home to some of the nation's most-loved programmes for over 40 years. In the studio gallery the vision mixer,

In the studio gallery the vision mixer,

In the days before video editing, complicated sequences, or items that required a lot of setting up, would always be recorded on to film. Film was a much more flexible medium than video tape, primarily because it could be easily edited.

In the days before video editing, complicated sequences, or items that required a lot of setting up, would always be recorded on to film. Film was a much more flexible medium than video tape, primarily because it could be easily edited.

An experimental session, testing new electronic effects for the series, had originally been planned for Friday 19th July, and it finally took place on Friday 13th September 1963, exactly 50 years ago today.

An experimental session, testing new electronic effects for the series, had originally been planned for Friday 19th July, and it finally took place on Friday 13th September 1963, exactly 50 years ago today.

Norman Taylor

Norman Taylor

Bernard Lodge

Bernard Lodge

A party celebrating the 50th anniversary of Doctor Who is to be held in London in November.

A party celebrating the 50th anniversary of Doctor Who is to be held in London in November. Radio Times is trying to find the nation's most-loved drama series, with Doctor Who featuring in the final shortlist.

Radio Times is trying to find the nation's most-loved drama series, with Doctor Who featuring in the final shortlist.

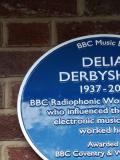

Grainer was an Australian composer who had been living in London for the past ten years. After working as a pianist in a nightclub, he had achieved some success as a composer, creating the scores for a number of TV series and a couple of features films. In 1961 he had won an Ivor Novello Award for the theme to Maigret, the series based on the books by Georges Simenon. Grainer had already worked with the Radiophone Workshop when creating his score for Giants of Steam, a documentary about railways.

Grainer was an Australian composer who had been living in London for the past ten years. After working as a pianist in a nightclub, he had achieved some success as a composer, creating the scores for a number of TV series and a couple of features films. In 1961 he had won an Ivor Novello Award for the theme to Maigret, the series based on the books by Georges Simenon. Grainer had already worked with the Radiophone Workshop when creating his score for Giants of Steam, a documentary about railways. Assigned to create the music would be one of the Radiophonic Workshop's staff,

Assigned to create the music would be one of the Radiophonic Workshop's staff,  Another important element of the show would be the special sounds. In charge for the first episode would be

Another important element of the show would be the special sounds. In charge for the first episode would be